|

Global

changes in the Earth's climate and chemistry of the ocean

threaten to further stress coral reefs at a time

when they are already declining due to local and

regional stressors including high nutrient and

sediment loading; unsustainable harvesting of

fish, corals and other reef organisms; and,

physical damage from boats, diving and

destructive fishing practices. While reefs have

survived large fluctuations in climate during

their 200 million years on earth there were mass

extinction events and long periods of time when

reefs were much less extensive than they are

today. We may be heading toward such a period

now. The question that needs to be asked is,

"should we try to do something about it?" Much

is at stake. Coral reefs provide ecological

services worth many billions of dollars in the

form of habitat for valuable fisheries, natural

protection from shoreline erosion, potential

source of new medicines and biomedical, and recreation. Coral

reefs contribute over one billion dollars each

year to the economy of south Florida alone. The

global nature of greenhouse warming and the

acidification of the ocean means that coral reef

preservation and restoration efforts based on

the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs)

may not be effective because the encroachment of

warm, acidic water will not respect park

boundaries. If we want to protect coral reefs

from the threats of global change we will need

to get serious about cutting the emissions of

carbon dioxide that are creating the threat. Global

changes in the Earth's climate and chemistry of the ocean

threaten to further stress coral reefs at a time

when they are already declining due to local and

regional stressors including high nutrient and

sediment loading; unsustainable harvesting of

fish, corals and other reef organisms; and,

physical damage from boats, diving and

destructive fishing practices. While reefs have

survived large fluctuations in climate during

their 200 million years on earth there were mass

extinction events and long periods of time when

reefs were much less extensive than they are

today. We may be heading toward such a period

now. The question that needs to be asked is,

"should we try to do something about it?" Much

is at stake. Coral reefs provide ecological

services worth many billions of dollars in the

form of habitat for valuable fisheries, natural

protection from shoreline erosion, potential

source of new medicines and biomedical, and recreation. Coral

reefs contribute over one billion dollars each

year to the economy of south Florida alone. The

global nature of greenhouse warming and the

acidification of the ocean means that coral reef

preservation and restoration efforts based on

the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs)

may not be effective because the encroachment of

warm, acidic water will not respect park

boundaries. If we want to protect coral reefs

from the threats of global change we will need

to get serious about cutting the emissions of

carbon dioxide that are creating the threat.

NCORE's global

change initiative will focus on understanding

the science behind the effects of rising

temperature and falling pH on corals and other

reef organisms. Studies will include analysis

of the geological record, geochemistry of corals

and forams, short and long term micro- and

mesocosm studies, field based observations and

manipulations.

Langdon, C., and M.J.

Atkinson. 2005.

Effect of

elevated pCO2 on photosynthesis and

calcification of corals and interactions with

seasonal change in temperature/ irradiance and

nutrient enrichment,

J. Geophysical

Res., 110, C09S07,

doi:10.1029/2004JC002576.

Langdon, C.

Effect of elevated CO2

on the cycling of organic and inorganic carbon

on coral reefs.

(OCCC meeting presentation, 1-4 Aug 2005,

Woodshole, MA).

|

|

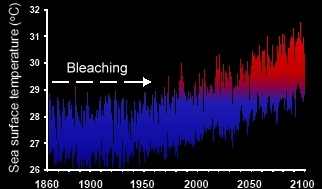

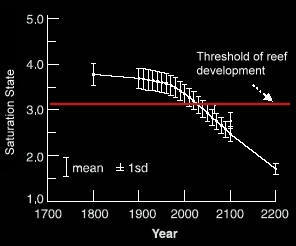

Greenhouse warming and ocean

acidification threaten to push corals beyond their environmental limits

within the next 50-100 years.

A: Sea surface temperatures are trending to levels that will regularly

exceed the bleaching threshold of many coral species (Hoegh-Gulberg, O.,

in press).

B: Ocean acidification is

driving down the saturation state of seawater. This parameter controls

the calcification rate of corals. If the trend continues, a threshold

may be crossed where corals will no longer be able to calcify quickly

enough to build corals (Kleypass, J.A., et al, 1999).

References

Hoegh-Guldberg,

O., Low coral cover in a high-CO2

world, J.

Geophysical Res., in press.

Kleypas, J.A.,

R.R. Buddemeier, D. Archer, J.P. Gattuso, C.

Langdon, and B.N. Opdyke, Geochemical

consequences of increased atmospheric CO2

on corals and coral reefs,

Science,

284,

118-120, 1999.

|

|